Retired teachers turn tutors to help students catch up

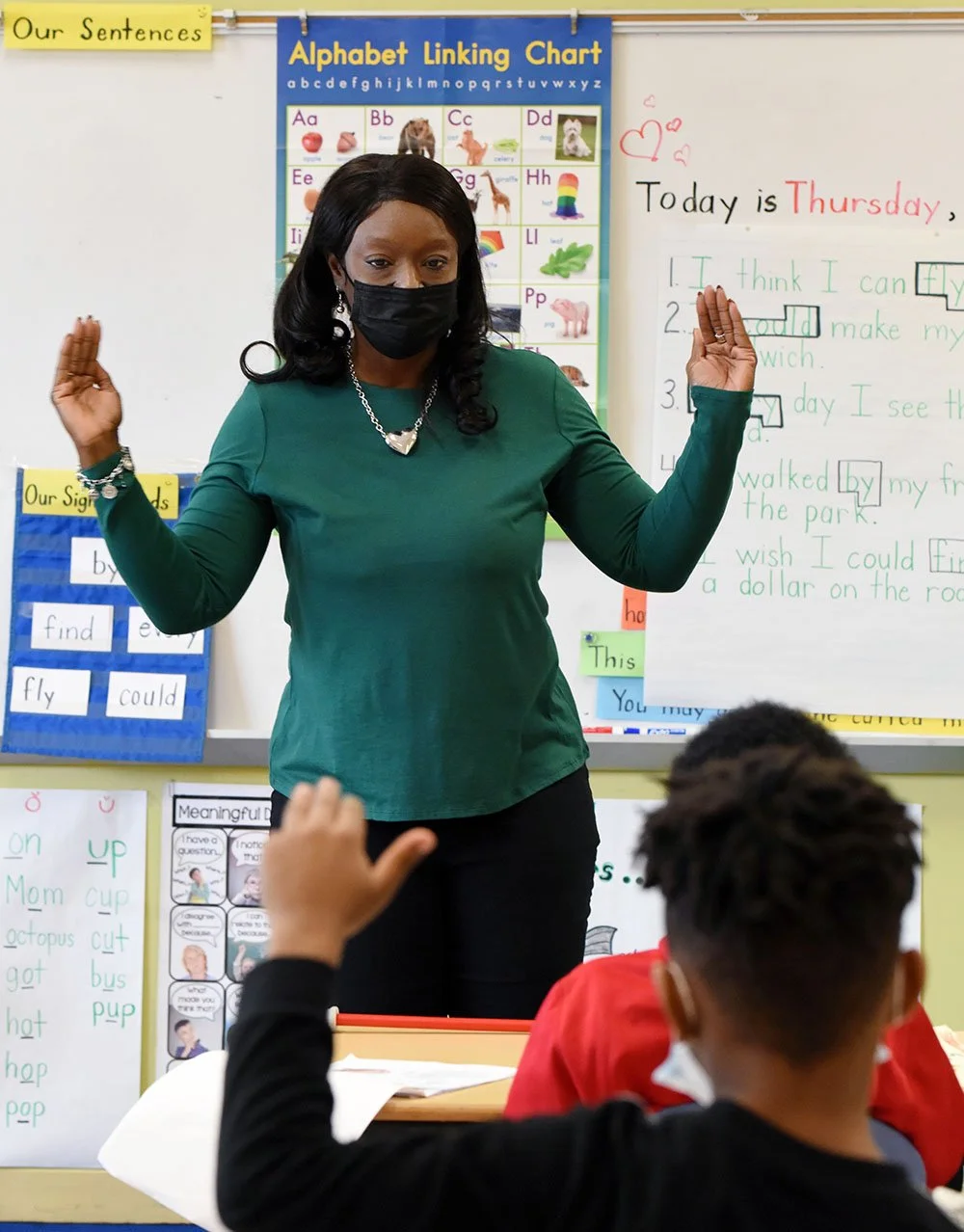

Twanna Fisher Warren retired after teaching for two decades, but she returned to the classroom as part of LCPS’s interventionist program, which connects small groups of students with tutors like Warren for regular, intense, in-school sessions designed to make up learning time lost to the pandemic. Here, she’s working on literacy skills with six first graders at Northeast Elementary during a session in February.

Not long after the luncheon celebrating Twanna Fisher Warren’s retirement from the classroom, her principal at Northeast Elementary School began talking to her about coming back to work part-time as a special kind of tutor.

When the principal, Rashard Curmon, called several months later to renew his recruitment pitch, after Warren had “taken the break I needed,” Northeast’s offer looked more like an invitation. “I thought about it and said, ‘Lord, am I supposed to go back and help these children?’ And He said yes. It was just that simple,” Warren said. “I came back with full intention of doing whatever needed to be done to help fill the gap that had been exaggerated by everything our world has gone through.”

What the world has gone through, of course, is the coronavirus pandemic, a once-in-a-century health threat that, among many serious consequences, upended education routines, robbed students everywhere of significant learning time and left them lagging against achievement goals.

It was not a situation that Lenoir County Public Schools avoided, but rather one the district recognized early on and has taken decisive steps to reverse.

The key to this effort, which the district calls intervention, are people like Twanna Fisher Warren – seasoned educators who have come out of retirement or work extra hours during the school day to provide intense small-group instruction to students who, according to test results and their teachers, would most benefit from the additional help.

The high-impact tutoring, which focuses on reading and math, is active in all LCPS schools. It is data-driven and scrupulously monitored. So principals and district administrators leading the intervention program can say with confidence that it’s working. How well, they will know next week when state-mandated standardized testing begins.

“I feel we’ve been able to close a lot of gaps in learning and we’re on target to show a lot of growth,” Curmon, the Northeast principal, said. “The data support we are moving in the right direction.”

The program launched districtwide in October, funded by a portion of the ESSER money the federal government has provided school districts to help allay the impact of the pandemic. The money pays the salaries of up to 84 interventionists and will be sufficient to keep the program going next school year.

Already, LCPS is strengthening the interventionist program for 2022-2023 by standardizing the approach across the district. Diane Heath, a retired principal who worked for more than 30 years with LCPS, came on board this month as the district’s interventionist coordinator and plans are to name grade-level coordinators to ensure all schools are served equally.

“The district is committed to two years. Beyond that, we’re going try to figure out a way to keep it going,” Moss Hill Elementary School principal Jeremy Barnett said. “Our structure is in place. We know what works and we adjusted things that we needed to. Going into next year, I feel like we’re going to hit the ground running.”

That was Curmon’s thinking last summer when he began recruiting and training interventionists for an in-school tutoring program that debuted about a month ahead of the districtwide program.

“I knew I needed to do something to reach kids because they’d been out of school with the broken school year,” he said. “We wanted to create a plan where we started the first week with identifying students who needed help the most, using last year’s data.”

Northeast employs six interventionists who work with groups of six or fewer students for 45 minutes at least three times a week during school hours. The number of interventionists vary among schools but the program’s framework – the commitment to a consistent schedule of small-group, individualized instruction – is standard across LCPS. So is the reliance on student evaluation tools that allow interventionists to tweak their instruction and principals to judge their program’s effectiveness.

“The beauty of this program is that our schedule allows us not only to teach and have the small group and be effective, but it also allows us to have the time to go back and do some really serious data dives and look at who’s growing, who’s not and what areas do we need to go back to revisit,” said Warren, whose focus as an interventionist is improving the literacy skills of Northeast first graders.

Retired teacher and principal Herman Greene helps a fourth grader at Northeast Elementary with a math problem involving fractions during one of his regular interventionist sessions in February.

Those adjustments are typically made in conjunction with the student’s classroom teacher, according to Michael Moon, principal of EB Frink Middle School. “If teachers see their student is struggling with a particular standard, they communicate with that interventionist and let them know where the struggles are and what they need to work on. We established that line of communication,” he said.

At Northeast, interventionist Herman Greene sits in on a teacher’s lesson. “I want to make sure we’re all on the same page. I want to teach it like the teachers are teaching it,” said Greene, who taught for 19 years and served as an assistant principal and principal for another 22.

In late February, fourth grade math classes were studying fractions and third graders were studying area, volume and perimeter, so those subjects were the focus of Greene’s two small groups dedicated to math. His two other tutoring groups concentrated on literacy goals – vocabulary, analyzing skills, “whatever the teachers are doing in the room,” he said.

“All our interventionists meet consistently with specific groups (of students) and document daily who received the assigned intervention,” Stacy Cauley, the district’s director of elementary education, said. “We feel like it’s very important that those same interventionists meet with those same children. That way they build the relationship and that interventionists know exactly what that student is struggling with and what they’re excelling at and are able to address that.”

Kathy Ham engages a student with a word recognition game at Moss Hill Elementary in April. She left a director-level position with the private sector to come back to LCPS as an interventionist.

Kathy Ham, who taught for 13 years at South Lenoir High School before taking her skills to the private sector, gave up a job as director of education for a regional behavioral health corporation to come back as an interventionist. At Moss Hill Elementary, she tutors third, fourth and fifth graders in basic reading skills.

“I worked with high school kids as a special education teacher, but most of them had skills deficits that are like the deficits I’m seeing with this age group,” Ham said. “Being able to give them direct attention on one deficit is awesome. I’ve been amazed at the growth the school has been able to measure.”